Maybe you’re a full-time student trying to come up with next month’s ramen budget. Perhaps you’ve just lost your job and you’re trying to earn a few bucks in between interviews. Or it could be you’re just happy to find a career doing something you’re really good at. For whatever reason, thousands of men donate sperm every year. Most of them expect a certain level of anonymity that no longer exists.

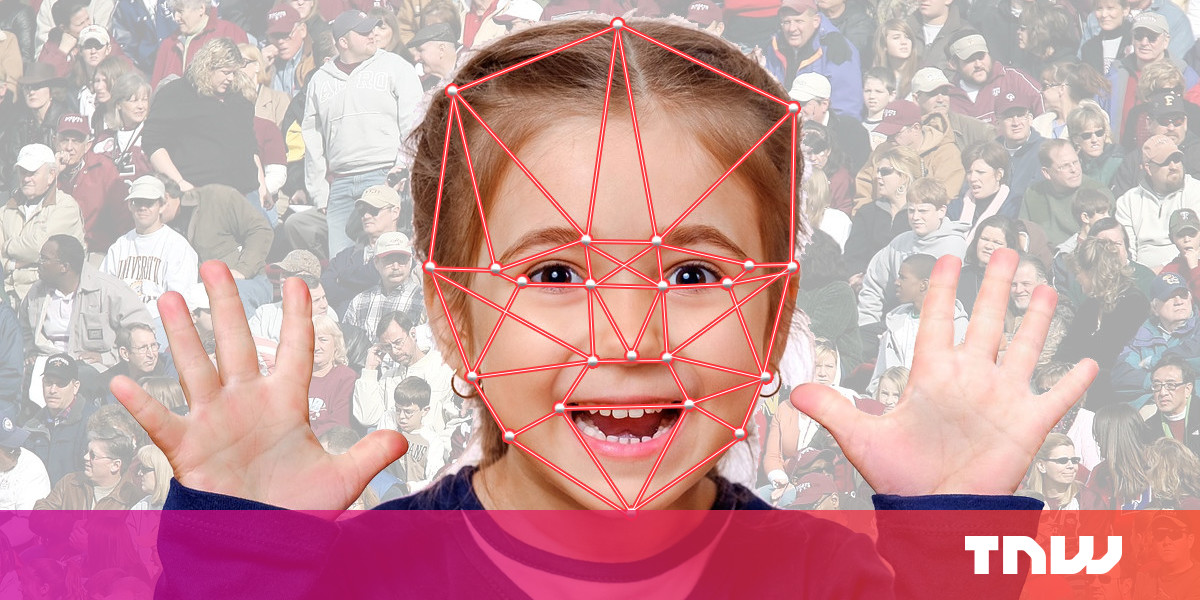

The biggest current threat to sperm donor anonymity continues to be online genealogy services capable of outing donors through DNA testing. But there’s a much larger shadow looming on the horizon that will make it even easier for people to disregard donor’s wishes to remain mysterious: facial recognition AI.

Genetic testing is more accessible than ever. But the clever application of legal threats, and the fact that families with children conceived via donor-provided sperm can only out donors one at a time, makes it the equivalent of hunting with a single-shot musket. There are no guarantees a family can find their kids’ biological father through the use of an online genetic test.

Facial recognition, on the other hand, will soon eradicate the idea of anonymity in general, and especially in fields related to genetics. The combination of consumer genetic testing, machine learning, and facial recognition will make it possible for anyone to predict who their biological parents – or even distant relatives – are with a heretofore unimaginable level of accuracy.

What happened

The entire concept of insemination via donor sperm was turned on its head in 2006 when 23andMe brought genetic testing and interpretation to the consumer market. For the first time in history, families could reverse engineer the genetic profiles of children conceived via donor sperm, and thus narrow down some members of a child‘s paternal family tree.

The problem of anonymity in donor sperm insemination procedures is as old as the practice itself. The first recorded donor sperm insemination in the US occurred in 1884. The doctor(s) performing the procedure maintained such a level of anonymity that the patient – the mother – didn’t know she was being impregnated with the sperm of men who weren’t her husband. The husband, reportedly, wasn’t sure what was going on either.

Today’s not much different

It’s no wonder, in the wake of such hideous 19th and 20th century medical and business practices, that families would have concerns over the validity of information they’ve been given by modern for-profit sperm banks.

You might think you selected a donor that was a Mensa-certified doctor only to find out that the sperm bank merely offered the illusion of choice, and your child’s donor wasn’t the prime specimen you thought. And, for families with children suffering from health issues, finding out who the actual donor is could be a matter of life and death.

Up until recently this meant that whatever a sperm bank told a family was all they’d ever know. If they’d been lied to, there was little chance they’d ever find out. But, the field of consumer DNA-testing exploded in 2006 when 23andMe, a company with family ties to Google, flung its doors open to a public eager to learn about its own ancestry. And with it, a large portion of donor’s anonymity was lost.

It didn’t take long for people to use these services to track down their biological parents. Unfortunately the sperm donor industry was built on the promise of anonymity. Despite laws ensuring children can seek out their biological parents once they reach the age of 18, sperm banks are likely to sue parents who use DNA services as a way of bypassing the donor’s wishes – whether intentional or not.

It’s now a legal issue

The New York Times recently published an article telling the story of Danielle Teuscher, a mother who discovered the identity of the biological paternal grandmother of her child after ordering a genetic test from 23andMe. When she contacted the grandmother to see if they were interested in meeting, things went south. Teuscher told the Times:

I wrote her and said, ‘Hi, I think your son may be my daughter’s donor. I don’t want to invade your privacy, but we’re open to contact with you or your son.’ I thought it was a cool thing.

Evidently the anonymous donor’s family and the sperm bank didn’t take too kindly to Teuscher’s allegedly “flagrant” circumvention of the donor anonymity system. The bank sent an email including the following strongly-worded passage:

Upon further investigation, we may be entitled to additional monetary damages if you have used other ancestry DNA programs, facial recognition tools on the internet or any other means, directly or indirectly, to contact or seek the identity of the donor.

Teuscher was threatened with more than $20K in damages in the company’s warning letter – something she says she never expected.

Enter AI

For people who were conceived through artificial insemination, involving donor sperm, the concerns are as real as their physical and mental health. Mistakes in paperwork, deception by sperm banks, and/or misreporting on the part of the donor has made any promises or guarantees made by many companies worthless.

And, for donors, it’s just as bad. Technology has rendered anonymity obsolete. A research paper published last year indicates the only solution may be to change how sperm banks and those performing insemination procedures counsel those providing sperm donations. In short, the researchers believe it’s already time we started informing donors that they aren’t anonymous anymore. And this includes people who may have donated decades ago. The only thing currently protecting individual donors is the threat of legal action.

AI will soon destroy that final vestige of anonymity. Machine learning has rapidly advanced the study of DNA phenotyping – predicting certain physical traits a person will have based on their DNA. In essence, a person could order a DNA test from a company like 23andMe and use DNA-phenotyping algorithms to predict certain physical features their relatives would have. The combination of data (the DNA profile) and machine learning (AI that produces predictions based on phenotype indicators) could provide a portrait of a person with higher accuracy that most facial recognition systems require to match an unknown face with one associated with an identity.

The scary part

This method could take an image created through DNA phenotyping-based predictions and then use a minimal amount of data – when was a child born, what sperm bank was the donation pulled from – to determine likely candidates for paternity. And, if you’ve ever had your DNA tested, your personal genetic data is probably already public.

Companies like 23andMe share what they call “anonymized data” with other companies – make no mistake, these kinds of companies tend to make the bulk of their money selling data not DNA testing kits.

DNA-phenotyping can take this anonymous data and figure out who it belongs to. And that means that, unless we can assume total trust for sperm banks, DNA-testing startups, and the medical community at-large our DNA harbors absolutely no anonymity.

The world needs sperm donors — some 30K to 60K kids are conceived every year through donor-based artificial insemination — but the question remains: how likely are men to continue donating once they know there’s no more anonymity?

Be the first to comment