The New Horizons probe has just sent back its first real shots of Ultima Thule, a 21-mile-long rock or planetesimal deep in the reaches of the solar system — and now the most distant object ever visited up close by mankind. The principal investigator of the mission, Alan Stern, called the accomplishment “a technical success beyond anything ever attempted before in spaceflight.”

Ultima Thule is, as early occultation studies suggested with remarkable success, what’s called a contact binary object, composed of two individual objects fused together likely through impact billions of years ago — and it’s the first ever photographed up close. This is like candy for planet scientists: learning about the creation and characteristics of this interesting type of object is a chance decades — nay, centuries — in expectation.

“We think what we’re looking at is perhaps the most primitive object that has yet been seen by any spacecraft, and may represent a class of objects that are the oldest and most primitive objects that can be seen anywhere in the solar system,” said NASA Ames’s Jeff Moore, geology and geophysics lead on New Horizons.

This slide in NASA’s presentation shows how Ultima Thule is speculated to have formed.

It’s formed of two lobes, the larger and smaller of which are named Ultima and Thule respectively, which likely accreted individually in the earliest days of the solar system, then entered each other’s influence and eventually encountered one another, fusing.

But Ultima Thule was chosen as the next target just before New Horizons buzzed Pluto not because it’s particularly interesting in itself, but because every object out there is interesting — we’ve never been up close to one! Instead, this particular rock, called MU69 when it was first identified by the Hubble during a frantic two-week search, happened to be something that the probe could swing by with minimal fuel expenditure.

“As the principal investigator I’ll say I’m surprised that, more or less picking one Kuiper Belt object out of the hat, we were able to get such a winner as this, that’s going to revolutionize our knowledge of planetary science,” Stern said.

Once it was decided — though at the time, the team had no idea how compelling MU69 would turn out to be — New Horizons altered its course to come within a few thousand miles of the object, close enough to get detailed imagery.

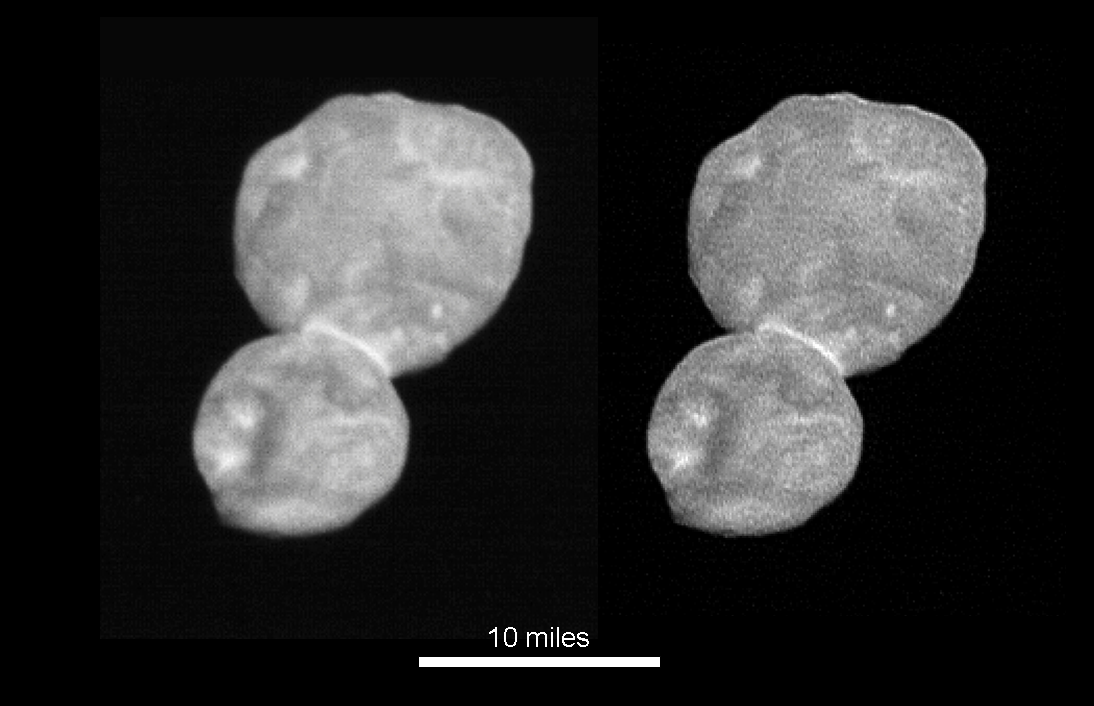

Until today we’ve only had pictures taken from very far away with the probe’s Long Distance Reconnaissance Imager, or LORRI, which produced tiny monochrome shots a few pixels across:

Great for mission control, but not for the front page. But remember that the probe was perhaps half a million miles away when it took the above images (on December 31), plus it was traveling at a relative speed of about 32,000 miles per hour. And of course there’s no good Wi-Fi out in the Kuiper belt — the data has to be painstakingly relayed back through the Deep Space Network.

The image at above was taken while the probe was much closer — about 50,000 kilometers. LORRI still produces the best details, but at that range the team can bring Ralph into play, which added the color you see.

Ralph is a set of multispectral imagers covering a variety of wavelengths and resolutions. These more-detailed images necessarily require more data to be sent home, and often need to be interpreted or tweaked by the science team in order to create a reasonable representation of what a human might see if we happened to be rolling past Ultima Thule.

The object is “about as reflective as garden variety dirt,” and of a reddish tint the team thinks may be the result of exposed volatile substances. There’s tons of variation and terrain on the surface, which we’ll get much better imagery of in time. These are just the initial shots, and New Horizons will be sending its data back for more than a year.

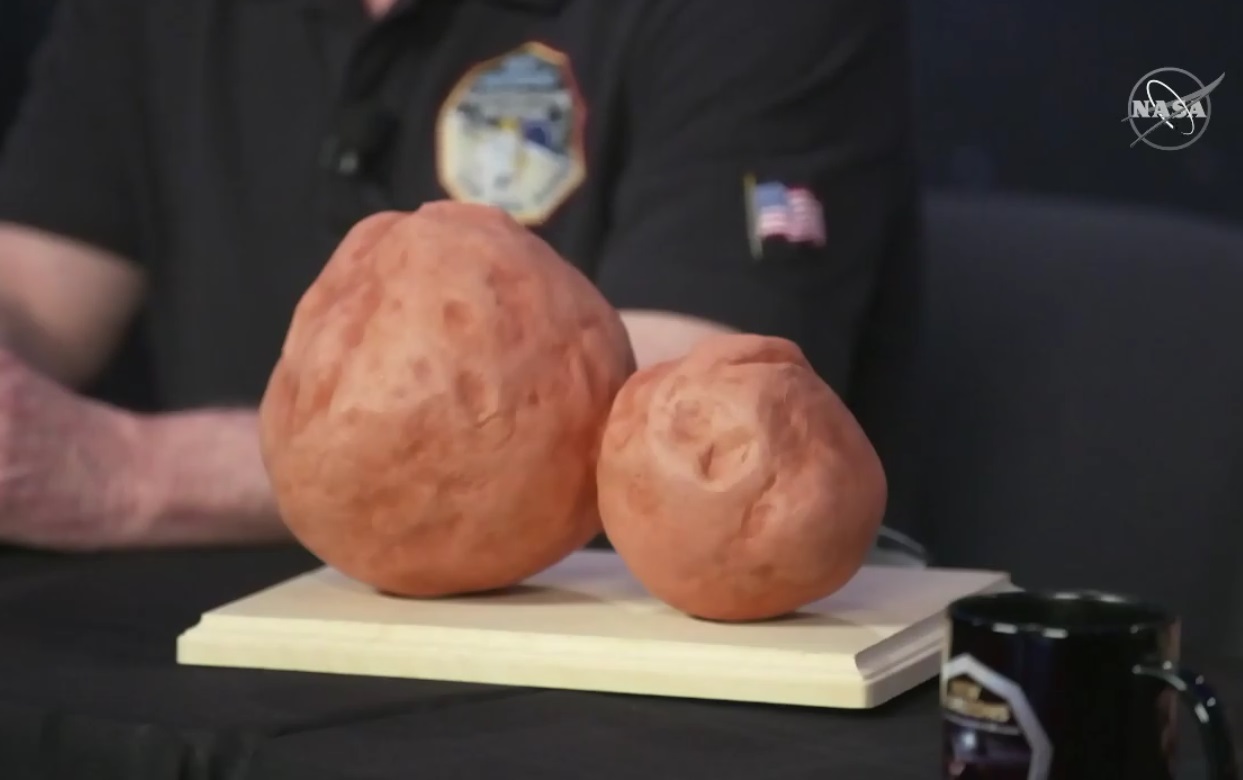

It was enough, however, to make some rather potato-like rough models of the object:

These shots are “just the tip of the iceberg,” Stern said. “We have far less than one percent of the data.”

“The current best picture that we have I believe has 20,000 or 28,000 pixels on the target, which way beats the six pixels we showed you last time,” he continued. “But ultimately if everything worked just right… the highest resolution image set that we took, it’ll have 35 meter resolution — it’ll ultimately be a megapixel image. It’s just going to get better and better.”

The team will continue to receive and collate data and will surely hold more press conferences as they learn more, and even more detailed imagery arrives.

The New Horizons probe itself — still hurtling outwards at 32,000 MPH — could continue to operate for another 15 or 20 years, and has fuel to change its course to perhaps find another target, but that’s all a matter of speculation for now. Stay tuned over the next year, the team suggested, but for now they’re focused on the data from Ultima Thule.

Be the first to comment