The continuing die-off of the world’s coral reefs is a depressing reminder of the reality of climate change, but it’s also something we can actively push back on. Conservationists have a new tool to do so with LarvalBot, an underwater robot platform that may greatly accelerate efforts to re-seed old corals with healthy new polyps.

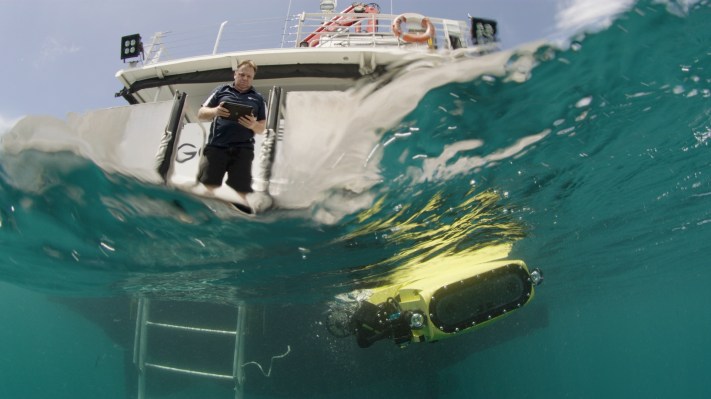

The robot has a history going back to 2015, when a prototype known as COTSbot was introduced, capable of autonomously finding and destroying the destructive crown of thorns starfish (hence the name). It has since been upgraded and revised by the team at the Queensland University of Technology, and in its hunter-killer form is known as the RangerBot.

But the same systems that let it safely navigate and monitor corals for invasive fauna also make it capable of helping these vanishing ecosystems more directly.

Great Barrier Reef coral spawn yearly in a mass event that sees the waters off north Queensland filled with eggs and sperm. Researchers at Southern Cross University have been studying how to reap this harvest and sow a new generation of corals. They collect the eggs and sperm and sequester them in floating enclosures, where they are given a week or so to develop into viable coral babies (not my term, but I like it). These coral babies are then transplanted carefully to endangered reefs.

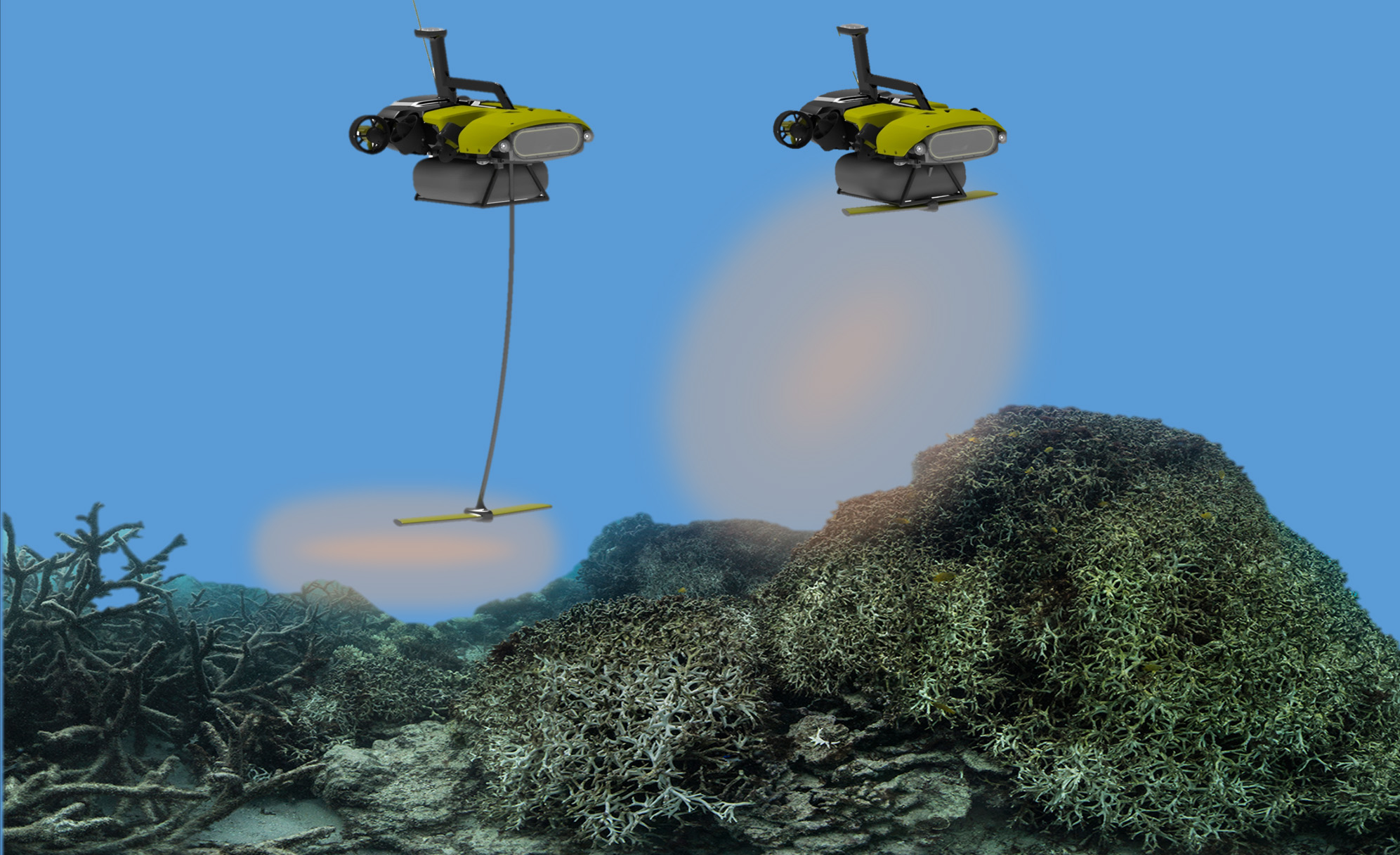

LarvalBot comes into play in that last step.

“We aim to have two or three robots ready for the November spawn. One will carry about 200,000 larvae and the other about 1.2 million,” explained QUT’s Matthew Dunbabin in a news release. “During operation, the robots will follow preselected paths at constant altitude across the reef and a person monitoring will trigger the release of the larvae to maximise the efficiency of the dispersal.”

It’s something a diver would normally have to do, so the robot acts as a force multiplier — one that doesn’t require food or oxygen, as well. A few of these could do the work of dozens of rangers or volunteers.

“The surviving corals will start to grow and bud and form new colonies which will grow large enough after about three years to become sexually reproductive and complete the life cycle,” said Southern Cross’s Peter Harrison, who has been developing the larval restoration technique.

It’s not a quick fix by any means, but this artificial spreading of corals could vastly improve the chances of a given reef or area surviving the next few years and eventually becoming self-sufficient again.

Be the first to comment