Sean Gallagher

Today, six prominent information-security experts who took part in DEF CON’s Voting Village in Las Vegas last month issued a report on vulnerabilities they had discovered in voting equipment and related computer systems. One vulnerability they discovered—in a high-speed vote-tabulating system used to count votes for entire counties in 23 states—could allow an attacker to remotely hijack the system over a network and alter the vote count, changing results for large blocks of voters. “Hacking just one of these machines could enable an attacker to flip the Electoral College and determine the outcome of a presidential election,” the authors of the report warned.

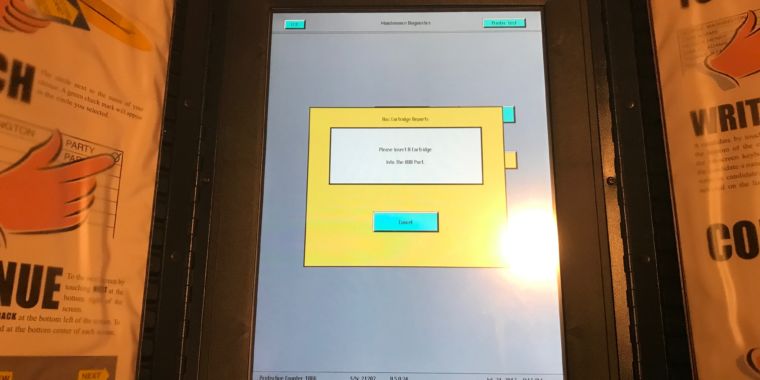

The machine in question, the ES&S M650, is used for counting both regular and absentee ballots. The device from Election Systems & Software of Omaha, Nebraska, is essentially a networked high-speed scanner like those used for scanning standardized-test sheets, usually run on a network at the county clerk’s office. Based on the QNX 4.2 operating system—a real-time operating system developed and marketed by BlackBerry, currently up to version 7.0—the M650 uses Iomega Zip drives to move election data to and from a Windows-based management system. It also stores results on a 128-megabyte SanDisk Flash storage device directly mounted on the system board. The results of tabulation are output as printed reports on an attached pin-feed printer.

The report authors—Matt Blaze of the University of Pennsylvania, Jake Braun of the University of Chicago, David Jefferson of the Verified Voting Foundation, Harri Hursti and Margaret MacAlpine of Nordic Innovation Labs, and DEF CON founder Jeff Moss—documented dozens of other severe vulnerabilities found in voting systems. They found that four major areas of “grave and undeniable” concern need to be addressed urgently. One of the most critical is the lack of any sort of supply-chain security for voting machines—there is no way to test the machines to see if they are trustworthy or if their components have been modified.

Yikes!

“If an adversary compromised chips through the supply chain,” the report notes, “they could hack whole classes of machines across the US, remotely, all at once.” And despite the claim by manufacturers that the machines are secure because they are “air gapped” from the Internet during use, testing over the last two years at DEF CON discovered remote hacking vulnerabilities requiring no physical access to the voting machines.

In a few cases, the Voting Village’s collection of hacker/researchers discovered that hacking the voting machines took less time than voting. One voting machine could be hacked in two minutes. And another hack, exploiting a flaw in an electronic card used to activate voting terminals, made it possible to reprogram the card wirelessly with a mobile device—allowing the voter to potentially cast as many votes as they like.

Perhaps the most frustrating of the problems documented by the researchers is that flaws, even when reported, don’t get fixed. One example is another vulnerability in the ES&S M650 that had been reported over 10 years ago to the manufacturer—but was still present on systems used for the 2016 election.

Be the first to comment