The Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General has dropped a 500-page report detailing its investigation into the conduct of FBI personnel, including former FBI Director James Comey, during the investigation into former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server (code-named “Midyear Exam”) and related events just before the 2016 presidential election. The report reveals details of the FBI’s internal communications, including an apparent agency-wide distaste for Lync, the mandated official messaging application for the FBI’s internal networks.

Sure to be a hot summer read for some in Washington, DC, the review does not find fault with the Justice Department’s decision not to pursue prosecution of Clinton or members of her staff, and it finds no evidence of political bias. But it does call out Comey and others for violations of policy and calls Comey’s decision to independently announce the results of the Clinton investigation as insubordination.

Comey immediately responded to the report in a New York Times opinion piece, stating that while he did not agree with all of the OIG conclusions, “I respect the work of his office and salute its professionalism. All of our leaders need to understand that accountability and transparency are essential to the functioning of our democracy, even when it involves criticism. This is how the process is supposed to work.”

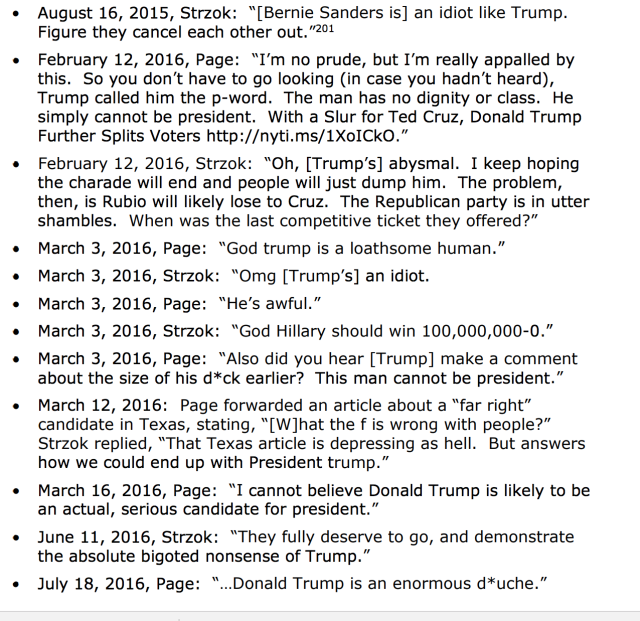

While the report mostly makes recommendations about clarification and adjustment of FBI policies and procedures, the investigators also recommended further review of the actions of some FBI agents who sent text messages with derogatory statements about then-candidate Donald Trump via FBI-owned mobile devices.

The heartbreak of autocorrect

The OIG inspection requested text messages between members of the Midyear Exam investigation team and found that the FBI retained only five days of messages on its text messaging platform: Microsoft Lync. The team also found that, on several occasions, some of the investigation team—including Deputy Assistant Director Peter Strzok, who was also involved in the investigation into Russian interference in the election, and FBI attorney Lisa Page—used personal email accounts and devices on some occasions to conduct official business. Both Strzok and Page blamed this largely on the horridness of the auto-completion and autocorrect features on their FBI-issued Samsung phones. Page told investigators:

[I]n particular, the autocorrect function is the bane of literally every agent of the FBI’s existence because those of us who care about spelling and punctuation, which I realize is a nerdy thing to do, makes us crazy because it takes legitimate words that are spelled correctly and autocorrects them into gobbledygook. And so, it is not uncommon for either one of us to just either switch to our personal phones or, or in this case, where it was going to be a fairly substantive thing that he was writing, to just save ourselves the trouble of not doing it on our Samsungs. Because they are horrible and super-frustrating.

Strzok also said that he on occasion forwarded documents to his personal computer to view them because he couldn’t see the markup in documents or properly edit them on his FBI-issued phone. The OIG investigators referred a decision on Strzok’s use of personal email to the FBI for a decision on whether he had violated policy; Page left the FBI in May of 2018.

The OIG took issue with Strzok’s and Page’s mixing of political expression with work over Microsoft Lync from their phones as well. Strzok was removed from Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s team last summer when questions were raised about the texts between him and Page, who were having an extramarital affair. The most critical text messages of them all were in an August 8, 2016 exchange:

Page stated, “[Trump’s] not ever going to become president, right? Right?!” Strzok responded, “No. No he’s not. We’ll stop it.”

Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General

As the election approached and then arrived (and passed), the messages became more despondent.

- November 3, 2016, Page: “The nyt probability numbers are dropping every day. I’m scared for our organization.”

- November 3, 2016, Strzok: “[Jill] Stein and moron [Gary] Johnson are F’ing everything up, too.”

- November 7, 2016, Strzok: Referencing an article entitled “A victory by Mr. Trump remains possible,” Strzok stated, “OMG THIS IS F*CKING TERRIFYING.”

- November 13, 2016, Page: “I bought all the president’s men. Figure I needed to brush up on Watergate.”

Several FBI agents who were not named in the report also expressed personal opinions. The OIG investigators wrote:

We do not question that the FBI employees who sent these messages are entitled to their own political views. However, we believe using FBI devices to send the messages—particularly the messages that intermix work-related discussions with political commentary—potentially implicate provisions in the FBI’s Offense Code and Penalty Guidelines. At a minimum, we found that the employees’ use of FBI systems and devices to send the identified messages demonstrated extremely poor judgment and a gross lack of professionalism. We therefore refer this information to the FBI for its handling and consideration of whether the messages sent by the five employees… violated the FBI’s Offense Code of Conduct.

So many leaks

The OIG also found that the FBI was full of leakers, with dozens of FBI agents having regular contact with media. This was not a result of poorly defined policy, the investigators found: “The FBI updated its media policy in November 2017, restating its strict guidelines concerning media contacts, and identifying who is required to obtain authority before engaging members of the media, and when and where to report media contact,” the office reported.

But while the policy itself was “clear and unambiguous,” the OIG team blamed a “cultural attitude” within the FBI for blatant disregard for the policy. “Accordingly, we recommend that the FBI evaluate whether (a) it is sufficiently educating its employees about both its media contact policy and the Department’s ethics rules and (b) its disciplinary penalties are sufficient to deter such improper conduct.”

The biggest communications faux-pas collection, however, was credited to Comey. The OIG report was especially critical of Comey’s decisions regarding release of information about the Clinton investigation and his decision to publicly announce his finding without discussing it first with Department of Justice leadership:

Comey admitted that he concealed his intentions from the Department until the morning of his press conference on July 5 and instructed his staff to do the same, to make it impracticable for Department leadership to prevent him from delivering his statement. We found that it was extraordinary and insubordinate for Comey to do so, and we found none of his reasons to be a persuasive basis for deviating from well-established Department policies in a way intentionally designed to avoid supervision by Department leadership over his actions.

This conclusion gives some cover after the fact for Comey’s dismissal, as does the OIG’s conclusions about Comey’s letter to members of Congress in late October regarding the Clinton emails found on the laptop of former Congressman Anthony Weiner. Comey sent the letter, he said, because he feared that if the details were not shared before the election, it would have been considered concealing of information to swing the election Clinton’s way—and a later disclosure would have tainted her administration.

But the OIG team rejected his logic:

Comey’s description of his choice as being between “two doors,” one labeled “speak” and one labeled “conceal,” was a false dichotomy. The two doors were actually labeled “follow policy/practice” and “depart from policy/practice.” Although we acknowledge that Comey faced a difficult situation with unattractive choices, in proceeding as he did, we concluded that Comey made a serious error of judgment.

There’s much more to mine from the OIG report. We’ll update this story with additional details as we discover them.

Be the first to comment