At the core of Facebook’s “well-being” problem is that its business is directly coupled with total time spent on its apps. The more hours you pass on the social network, the more ads you see and click, the more money it earns. That puts its plan to make using Facebook healthier at odds with its finances, restricting how far it’s willing to go to protect us from the harms of over use.

The advertising-supported model comes with some big benefits, though. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has repeatedly said that “We will always keep Facebook a free service for everyone.” Ads lets Facebook remain free for those who don’t want to pay, and more importantly, for those around the world who couldn’t afford to.

Ads pay for Facebook to keep the lights on, research and develop new technologies, and profit handsomely in a way that attracts top talent and further investment. More affluent users with more buying power in markets like the US, UK, and Canada command higher ad prices, effectively subsidizing the social network for those in developing nations where ad rates are lower.

Ads and the envy spiral

The issue is that the ad model rewards Facebook for maximizing how long we spend using it, often through passive content consumption via endless News Feed scrolling. Yet studies show that it’s this kind of zombie browsing that hurts us. Spending just 10 minutes passively consuming Facebook can make us feel worse.

Passive Facebook usage leads to envy, which leads to declines in life satisfaction

We fall into envy spirals. The study’s author wrote that “Continually exposing oneself to positive information about others should elicit envy, an emotion linked to lower well-being”. A 2011 study concluded “people may think they are more alone in their emotional difficulties than they really are” after browsing everyone’s manicured life highlights on Facebook.

This research has clearly had an impact on Zuckerberg, who explicitly announced on the Q3 2017 earnings call that “Protecting our community is more important than maximizing our profits . . . Time spent is not a goal by itself. We want the time people spend on Facebook to encourage meaningful social interactions . . . when people are spending so much time passively consuming public content that it starts taking away from the time people are connecting with each other, that’s not good.”

To that end, Zuckerberg has announced a slew of changes to Facebook, though they’ve been relatively minor. Facebook is showing fewer news articles, public posts, and viral videos while prioritizing what leads people to comment and interact with each other. The result was a 50 million hours per day reduction in how long people spend on Facebook. That might sound like a lot, but it’s actually only a 5 percent decrease. Discussing how to quantify what’s “meaningful”, Facebook’s VP of News Feed Adam Mosseri this week admitted that “We’re trying to figure out how to best measure and understand that.”

Making truly forceful changes could have a much more significant impact on time spent, and potentially ad revenue. That creates resistance to confronting people with how long they spend on its apps, reducing spammy reengagement notifications, or creating more powerful ‘do not disturb’ options.

Facebook Clear

And so, we have a company that wants to make us feel better but earns money off making us feel worse, and that promises to stay free despite the negative incentives inherent in ad-based business models.

That’s why I think Facebook should introduce an ad-free subscription option in addition to its existing ad-supported free service.

By charging a monthly fee to remove ads, Facebook could begin to decouple its business from time spent. This would allow it to keep revenue stable even while making bigger changes that enhance well-being while decreasing how long we spend on its apps.

It’s not a totally foreign idea for Facebook, as WhatsApp used to charge a $1 per year subscription in some countries. And Facebook could defend itself against election interference and other political meddling by offering an option to hide all ads.

For users who can afford the fee and want to pay, they’ll get a more purposeful experience on Facebook where they only see what’s organically surfaced in the News Feed. This would allow people to reclaim the time they waste viewing ads, and spend it having meaningful interactions with their friends and communities — thereby fulfilling Facebook’s mission.

For users who can’t afford the fee or don’t want to pay, their Facebook experience remains largely the same. But as the percentage of total users monetized by ads decreases, Facebook gains more flexibility in how it builds its apps to be more respectful of our mental health. And since it’s already reaching saturation in some markets, it’s less risky to refocus from growth to aligning monetization with its mission.

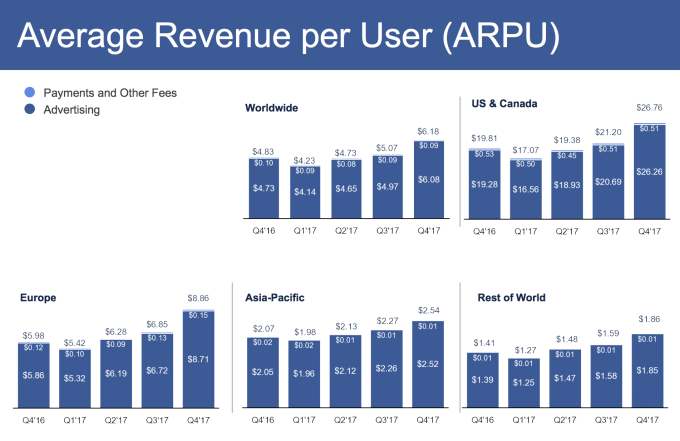

Facebook’s average revenue per user could be used to set a price for an ad-free version

Facebook could charge a similar rate to what it currently earns from users via ads (and the tiny amount it still gets from game payments). In the U.S., Facebook earned $84.14 per user, while earning an average worldwide of $20.21. Charging $1.65 per month, or even $7 per month to remove ads from Facebook could feel very reasonable to some users. The rate would increase yearly to stay in-line with ad revenue or follow its current growth trajectory. Facebook might only get a few percent of people to pay, but that would still be tens to hundreds of million people.

Syncing subscription prices without bonus options to revenue per non-subscriber would let Facebook continue to concentrate on developing features for everyone.

Facebook+

But getting a truly significant percentage of users shifting to subscriptions would likely require Facebook offering additional premium features beyond removing ads. Product and engineering talent and resources previously focused on ads could be redirected to this development.

Facebook would have to avoid reserving critical features for paid users otherwise it could make non-subscribers feel betrayed and slighted, like second-class social network citizens. This late in the game, it’d be tough to take anything away from existing users. Facebook couldn’t make its free version just a demo or shell of the paid version like Spotify, where only subscribers can choose what specific songs they hear.

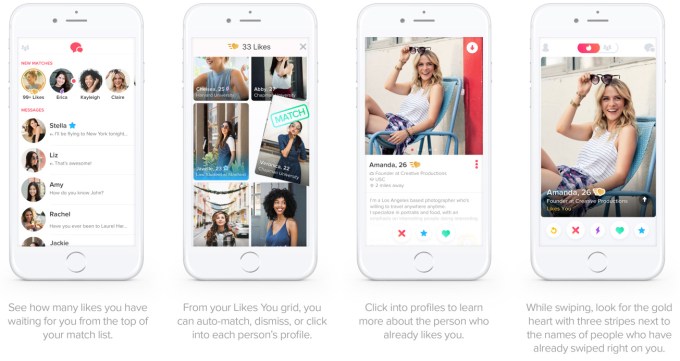

Instead Facebook would need to take cues from apps like Tinder, which charges extra for features like unlimited swipes, undo a swipe, and only seeing people who’ve already right swiped you. Gamer chat app Discord offers cosmetic boosts to your profile like choosing your display name, high resolution screen sharing, and animated profile avatars.

What could these bonus features look like on Facebook? It could offer similar cosmetic upgrades, such as a badge next to your user name to make you stand out like verified profiles, extra profile customization options, displayable virtual goods, or profile pic special effects. It could sell content quality improvements like higher resolution image and video uploads, or let people exceed the 5000 friend limit.

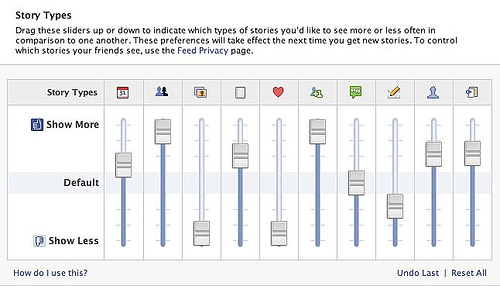

Or perhaps most appealing would be additional curation tools, like advanced manual controls for deciding what shows up in your News Feed — which Facebook used to offer. Back in 2007 you could filter out relationship status changes, links, photos, and more. I’m sure some people would happily shell out cash to banish baby photos or politics from their feed. If browsing unfulfilling content is one of the problems, selling additional controls could let people solve it for themselves.

Facebook’s manual News Feed curation controls from 2007 via GigaOm

If Facebook was desperate, it could meddle with privacy by providing a “see who views your profile” feature. People so constantly seek out that option that scams and phishing sites often tout offering the ability. LinkedIn sells it, after all. But there’s plenty to offer that wouldn’t interfere with the experience of anyone who doesn’t pay like this would.

Before The Backlash Grows

There’s little risk in testing the idea. Facebook is constantly running all sorts of feature experiments through its “Gatekeeper” system that lets it show slightly different versions of the service to different tiny subsets of users. Facebook could beta test subscriptions in a smaller English-speaking country like New Zealand that approximates the culture of its core markets but is more contained and less critical to its business than the U.S. If it can’t find the right feature set that makes people pay, scrap it.

One concern is that Facebook benefits from having a giant unified user base all accessible to advertisers who crave scale. The ability to hit a huge percentage of a demographic with promotions in a short time, such as for a new movie release, attracts advertisers to Facebook. That appeal could decrease if a portion of users subscribe and never see ads, with Facebook giving up more power to Google in their advertising duopoly.

But Zuckerberg has already committed to some short-term loss of profits in his quest to promote well-being. In the long-run, letting users pay if they want could keep them loyal while letting Facebook configure its News Feed algorithm for what enriches everyone. Building safeguards against overuse today could save Facebook from a stronger backlash in the future. Facebook should always be free, but letting some people pay could give Facebook the freedom to make itself a healthier part of our lives.

For more on the need for Facebook’s push into time well spent, read our feature piece “The difference between good and bad Facebooking”

Be the first to comment