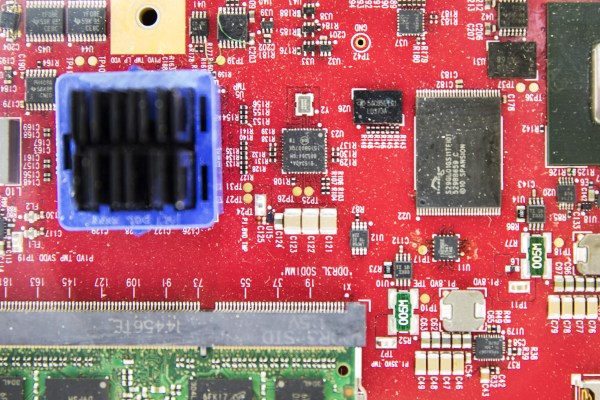

Thursday’s explosive story by Bloomberg reveals detailed allegations that the Chinese military embedded tiny chips into servers, which made their way into data centers operated by dozens of major U.S. companies.

We covered the story earlier, including denials by Apple, Amazon and Supermicro — the server maker that was reportedly targeted by the Chinese government. Apple didn’t respond to a request for comment. Amazon said in a blog post that it “employs stringent security standards across our supply chain.” The FBI and the Office for the Director of National Intelligence did not comment, but denied comment to Bloomberg. This is a complex story that rests on more than a dozen anonymous sources — many of which are sharing classified or highly sensitive information, making on-the-record comments impossible without repercussions. Despite the companies’ denials, Bloomberg is putting its faith in that the reader will trust the reporting.

Much of the story can be summed up with this one line from a former U.S. official: “Attacking Supermicro motherboards is like attacking Windows. It’s like attacking the whole world.”

It’s a fair point. Supermicro is one of the biggest tech companies you’ve probably never heard of. It’s a computing supergiant based in San Jose, Calif., with global manufacturing operations across the world — including China, where it builds most of its motherboards. Those motherboards trickle throughout the rest of the world’s tech — and were used in Amazon’s data center servers that power its Amazon Web Services cloud and Apple’s iCloud.

One government official speaking to Bloomberg said China’s goal was “long-term access to high-value corporate secrets and sensitive government networks,” which fits into the playbook of China’s long-running effort to steal intellectual property.

“No consumer data is known to have been stolen,” said Bloomberg.

Infiltrating Supermicro, if true, will have a long-lasting ripple effect on the wider tech industry and how they approach their own supply chains. Make no mistake — introducing any kind of external tech in your data center isn’t taken lightly by any tech company. Fear of corporate and state-sponsored espionage has been rife for years. It’s chief among the reasons why the U.S. and Australia have effectively banned some Chinese telecom giants — like ZTE — from operating on its networks.

Having a key part of your manufacturing process infiltrated — effectively hacked — puts every believed-to-be-secure supply chain into question.

With nearly every consumer electronics or automobile, manufacturers have to procure different parts and components from various sources across the globe. Ensuring the integrity of each component is near impossible. But because so many components are sourced from or assembled in China, it’s far easier for Beijing than any other country to infiltrate without anyone noticing.

The big question now is how to secure the supply chain?

Companies have long seen supply chain threats as a major risk factor. Apple and Amazon are down more than 1 percent in early Thursday trading and Supermicro is down more than 35 percent (at the time of writing) following the news. But companies are acutely aware that pulling out of China will cost them more. Labor and assembly are far cheaper in China, and specialist parts and specific components often can’t be found elsewhere.

Instead, locking down the existing supply chain is the only viable option.

Security giant CrowdStrike recently found that the vast majority — nine out of 10 companies — have suffered a software supply chain attack, where a supplier or part manufacturer was hit by ransomware, resulting in a shutdown of operations.

But protecting the hardware supply chain is a different task altogether — not least for the logistical challenge.

Several companies have already identified the risk of manufacturing attacks and taken steps to mitigate. BlackBerry was one of the first companies to introduce root of trust in its phones — a security feature that cryptographically signs the components in each device, effectively preventing the device’s hardware from tampering. Google’s new Titan security key tries to prevent manufacturing-level attacks by baking in the encryption in the hardware chips before the key is assembled.

Albeit at start, it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. Former NSA hacker Jake Williams, founder of Rendition Infosec, said that even those hardware security mitigations may not have been enough to protect against the Chinese if the implanted chips had direct memory access.

“They can modify memory directly after the secure boot process is finished,” he told TechCrunch.

Some have even pointed to blockchain as a possible solution. By cryptographically signing — like in root of trust — each step of the manufacturing process, blockchain can be used to track goods, chips and components throughout the chain.

Instead, manufacturers often have to act reactively and deal with threats as they emerge.

According to Bloomberg, “since the implanted chips were designed to ping anonymous computers on the internet for further instructions, operatives could hack those computers to identify others who’d been affected.”

Williams said that the report highlights the need for network security monitoring. “While your average organization lacks the resources to discover a hardware implant (such as those discovered to be used by the [Chinese government]), they can see evidence of attackers on the network,” he said.

“It’s important to remember that the malicious chip isn’t magic — to be useful, it must still communicate with a remote server to receive commands and exfiltrate data,” he said. “This is where investigators will be able to discover a compromise.”

The intelligence community is said to be still investigating after it first detected the Chinese spying effort, some three years after it first opened a probe. The investigation is believed to be classified — and no U.S. intelligence officials have yet to talk on the record — even to assuage fears.

Be the first to comment