By now many have heard of Amazon’s most audacious attempt to shake up the retail world, the cashless, cashierless Go store. Walk in, grab what you want, and walk out. I got a chance to do just that recently, as well as pick the brain of one of its chief architects.

My intention going in was to try to shoplift something and catch these complacent Amazon types napping. But it became clear when I went in that this wasn’t going to be an option. I was never more than a foot or two from an Amazon PR rep, and as Dilip Kumar, the projects VP of Technology, convinced me, they’d already provided against such crude attacks on their system.

As you might have seen in the promo video, you enter the store (heretofore accessible to Amazon employees only) through a gate that opens when you scan a QR code generated by the Amazon Go app on your phone. At this moment (well, actually the moment you entered or perhaps even before) your account is associated with your physical presence and cameras begin tracking your every move.

The many, many cameras.

I wondered when the idea of Amazon’s cashierless store was first proposed how it would be accomplished. Cameras on the ceiling, behind the display cases, on pedestals? What kind? Proximity and weight sensors, face recognition? Where would this all be collated and processed?

Amazon’s approach wasn’t as complex as I expected, or rather not in the way I expected. Mainly the system is made up of dozens and dozens of camera units mounted to the ceiling, covering and recovering every square inch of the store from multiple angles. I’d guess there are maybe a hundred or so in the store I visited, which was about the size of an ordinary bodega or gas station mart.

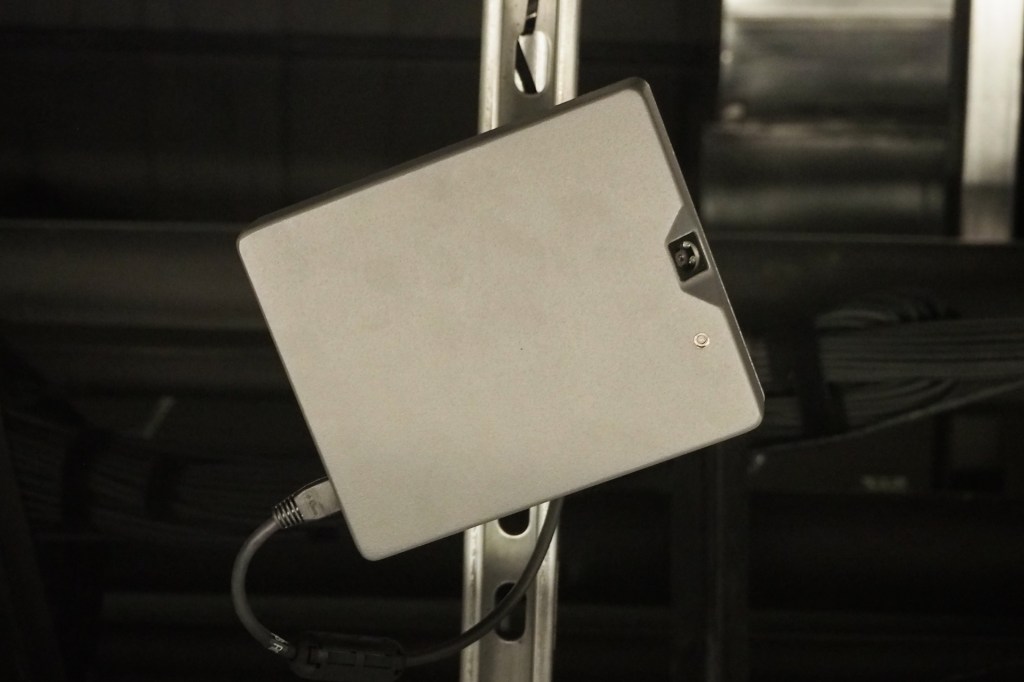

These are ordinary RGB cameras, custom made with boards in the enclosure to do some basic grunt computer vision work, presumably things like motion detection, basic object identification, and so on.

These are ordinary RGB cameras, custom made with boards in the enclosure to do some basic grunt computer vision work, presumably things like motion detection, basic object identification, and so on.

They’re augmented by separate depth-sensing cameras (using a time-of-flight technique, or so I understood from Kumar) that blend into the background like the rest, all matte black.

The images captured from these cameras are sent to a central processing unit (for lack of a better term, not knowing exactly what it is), which does the real work of quickly and accurately identifying different people in the store and objects being picked up or held. Picking something up adds it to your “virtual shopping cart,” and you can pop it in a tote or shopping bag as fast as you like. No need to hold it up for the system to see.

This is where the secret sauce is, Kumar told me, and I believe him. As banal a problem as it may seem to determine which similarly dressed person picked up which nearly identical yogurt cup, it’s very difficult to get right at the speed and accuracy level needed in order to base an entire business on it.

A student, after all, with the resources available these days, could probably design a version of this store in a few weeks that would work 80 percent of the time. But to get it right 99.9 percent of the time, frictionlessly and instantly, is a challenge that requires a great deal of work.

Notably, there is no facial recognition used (I asked). Amazon perhaps sensed early on that this would earn them rebuke from privacy-conscious shoppers, though the idea of those people coming to this store strikes me as unlikely. Instead, the system uses other visual cues and watches for continuity between cameras — you’re never not in sight of a lens, so it’s easy for the system to see a shopper move from one camera to another and make the connection.

Should there be a technical problem with a camera or it gets sauce on its lens somehow, the system doesn’t break down entirely. It’s been tested with cameras missing, though naturally it wouldn’t be long before a replacement is put in place and the system re-re-calibrates.

In addition to the cameras, there are weight sensors in the shelves, and the system is aware of every item’s exact weight — so no trying to grab two yogurts at once and palm the second, as I considered trying. You might be able to do it Indiana Jones style, with a suitable amount of sand in a sack, but that’s more effort than most shoplifters are willing to put out.

In addition to the cameras, there are weight sensors in the shelves, and the system is aware of every item’s exact weight — so no trying to grab two yogurts at once and palm the second, as I considered trying. You might be able to do it Indiana Jones style, with a suitable amount of sand in a sack, but that’s more effort than most shoplifters are willing to put out.

And, as Kumar noted to me, most people aren’t shoplifters, and the system is designed around most people. Building a system that assumes ill intent rather than merely detecting discrepancies is not always a good design choice.

There is in fact a human in the loop should the system find itself in a bind, but Kumar said this was rare enough that it hardly needed to be considered. He also said that the difficulty of monitoring the store doesn’t increase with square footage, though of course you’ll need more cameras and more processing power.

It’s also been tested with serious crowds; we were there during a slow time in the mid-afternoon, but shortly before that was the lunch rush, they told me, when dozens rather than a handful of people could be found walking in and out without doing anything more than showing their phone to a sensor at the entrance.

It’s also been tested with serious crowds; we were there during a slow time in the mid-afternoon, but shortly before that was the lunch rush, they told me, when dozens rather than a handful of people could be found walking in and out without doing anything more than showing their phone to a sensor at the entrance.

There may not be cashiers, but there are staff: stockers who replenish inventory; an ID checker (and erstwhile sommelier I’m sure) in the wine and beer section, and chefs in the back throwing together fresh sandwiches and meal kits. Someone also hovers in the entrance area to help people with the app, answer questions, and take returns.

The selection was mainly grab-and-go lunches and snacks, with the usual handful of household items you grab at the bodega on the way home. Prices were what you’d expect at a supermarket rather than a convenience store, though.

As for the expected Amazon gambits that leverage its existing properties and hooks, few are to be found. The app is self-contained, and your purchases are tracked there rather than on your “main” Amazon account. Prime members don’t get lower prices. Whole Foods has a little section of its own but there’s no broader partnership (and no plans to convert any of those stores to Go, though I can’t imagine why not).

Overall I’m impressed with the seamlessness of the system, and I can see these things successfully operating here and there.

Overall I’m impressed with the seamlessness of the system, and I can see these things successfully operating here and there.

On the philosophical side, I’m troubled, of course — a convenience store you just walk out of is a friendly mask on the face of a highly controversial application of technology: ubiquitous personal surveillance.

It’s a bit overkill, I think, to replace a checker or self-checkout stand with a hundred cameras that unblinkingly record every tiny movement. What’s to gain? 20 or 30 seconds of your time back? Lack of convenience has hardly been a complaint for this market — it’s right there in the name: “convenience store.”

Like so many ways companies are applying tech today, this seems to me an immense amount of ingenuity and resources being used to “solve” something that few people care about and fewer still consider a problem. As a technical achievement it’s remarkable, but then again, so is a robotic dog.

The store works — that much I can say for it. Where Amazon will take it from here I couldn’t say, nor would anyone respond meaningfully to my questions along these lines. Amazon Go will be open to the public starting this week, but whether anyone will find it to be anything more than a novelty is yet to be seen.

Be the first to comment